DIGITAL ECONOMY AND BLUEPRINT

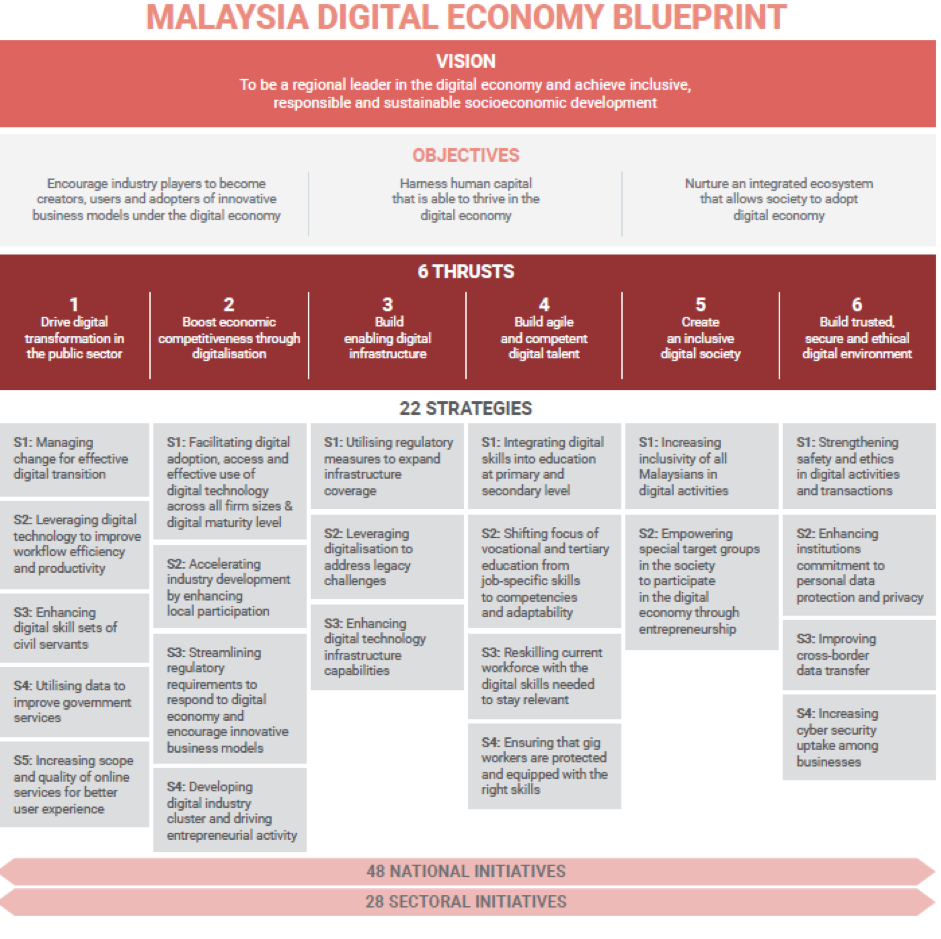

The Malaysia Digital Economy Blueprint/MyDIGITAL Blueprint Initiative (2021 – 2030) was launched on February 19, 2021. It is aimed at spearheading the development of Malaysia’s digital economy by harnessing the use of digital tools among the citizens and businesses in the country.

Digital transformation is the necessary outcome of a growing economy and the adoption of technology. Thus, the MyDIGITAL initiative is timely. It is supported by Malaysia Digital Economy Corporation (MDEC) to help make Malaysia a globally competitive digital nation through retraining and re-skilling initiatives that will bolster growing demands for digital skills and technologies. A good example is the #SayaDigital which MDEC has set up to help introduce reskilling in digital industries. Through this, employees are expected to progress rapidly in their acquisition of digital skills. This will help them stay relevant while strengthening their short-term and long-term competitiveness.

Cloud computing is one of the most fundamental infrastructures to enable a successful national digital transformation strategy. This is because, it will enable effective storage and access to data, services and applications while keeping investment costs competitive.

To that end, Microsoft, Google and Amazon alongside Telekom Malaysia Bhd have been named as the top four cloud hyperscalers that will be investing between RM12 billion and RM 15 billion over the next five years to build and manage hyper-scale data centres and cloud services in Malaysia[1]. This will help businesses accelerate their cloud adoption journey successfully.

Another step forward is the establishment of the National Investment Aspirations alongside the National Investment Council which is an excellent starting point. This will place Malaysia on par with the rest of the world given the fact that most countries are already capitalising on digital transformation in all aspects of the economy as they position themselves to be more competitive by adopting new tools and policies that are geared towards attracting investments as well as creating local development benefits.

According to a World Bank Report in 2019 (Figure 1), almost all governments in Southeast Asia have produced high-level plans at their country levels and are undergoing various stages of policies development and implementation.

In addition to the above, other coordinating agencies include the Malaysian Investment Development Authority (MIDA), Malaysian Administrative Modernisation and Management Planning Unit (MAMPU) and the Economic Planning Unit (EPU). MIDA has been promoting digital tech sectors such as data centres, cybersecurity, artificial intelligence (AI), creative and digital content. Similarly, the Akademi Sains Malaysia’s 10 Science, Technology, Innovation and Economy Framework (MySTIE) will also help to accelerate the socio-economic drivers and national niche areas that are crucial in building a sustainable tech-savvy workforce.

Companies should also diversify into high-value-added activities that could serve as their competitive edge. This may include investing in logistics and distribution infrastructure as well as leveraging the industrialisation of the Internet of Things (IoT) as a new source of economic growth.

Figure 1: Digital Economy Masterplan in Southeast Asia

Source: World Bank Report, 2019

Figure 2: Industry Evolution

Figure 3: Evolution of Digital Policies

As shown in Figures 2 and 3, the industry evolution begun in Malaysia in the late 1990s, commencing more prominently since Industry 3.0. Today, with Industry 4.0 we are embracing the various phases of digital, green, and circular economy, resulting in the master plan or blueprint of the Malaysia Digital Economy (Figure 4) launched in 2021.

The COVID-19 pandemic has spurred the digitalisation of services across the world and Malaysia is no exception. The way forward as seen by everyone around the world is the implementation of the national digital identity and the government’s commitment to open more opportunities for economic gains for institutions and citizens in the country. These include e-commerce and financial services, being the largest contributor to the digital economy in Malaysia, as well as government online services, and further improving telecommunications coverage and 5G capabilities in urban and especially rural areas. Technology has become far more essential than ever before. As a result, the digital economy has become a pillar for any economic policy planning. This is even more necessary given the fact that the economic landscape will change even more post-COVID-19, in line with the Industry 4.0 drive over the last few years.

The Malaysia Digital Economy Blueprint is a way forward to accelerate digital transformation and national investment innovations. This further shows the importance and urgency for employers to recognise this aspect and for employees to acquire different sets of skills to stay relevant by performing higher-value-added activities while automation of robots and machines perform repetitive and laborious tasks.

Thus, the new generation of employees must be agile and digital-ready in areas such as robotics and artificial intelligence (AI). They must be creators and innovators instead of mere users, followers, and adopters in the digital entrepreneurship industry. The current situation also demonstrates the need for creating re-skilling opportunities.

Figure 4: Masterplan of Malaysia’s Digital Economy Blueprint

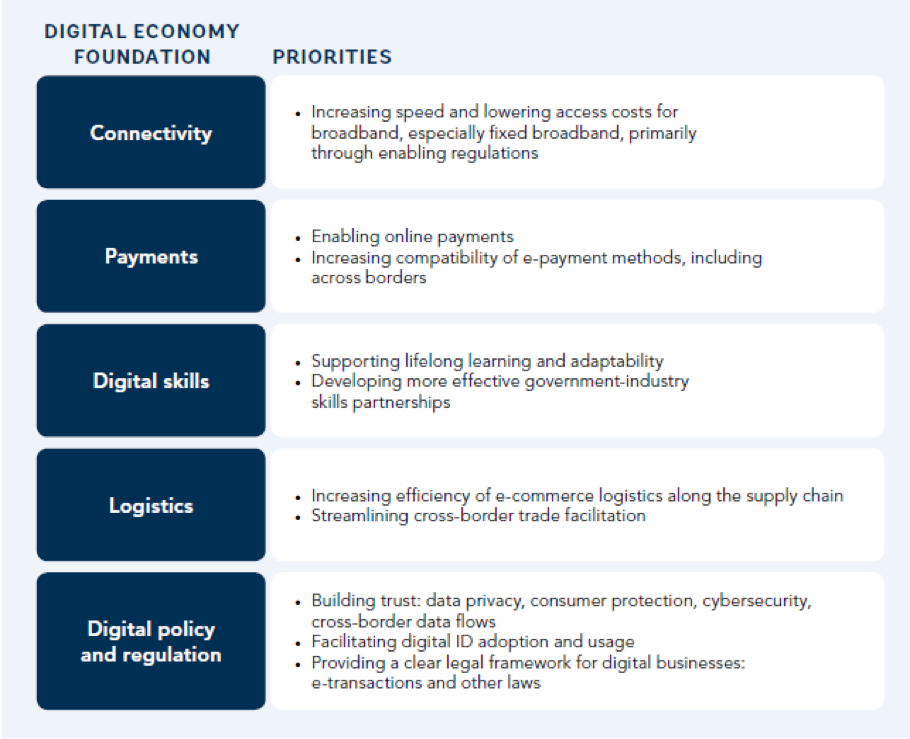

Figure 5 shows the foundations for building a digital economy across various sectors. It also highlights how by building a supportive macroeconomic and business climate, we will be able to unlock many opportunities of significant impact around areas such as financial and social inclusion as well as growth. Figure 6 summarises the enabling environment priorities in each foundation. Pertinent to the various levels of skills attainment, a different level of expertise is required as demonstrated in Figure 7 alongside other related aspects and examples.

Figure 5: Digital Economy

Source: World Bank Report 2019

Figure 6: Foundation of Digital Economy and its priorities

Source: World Bank Report 2019

Figure 7: Skills relevant for the Digital Economy

Source: World Bank Report 2019

Figure 8: Employment share in the economy – low, medium, and high skilled employment as a percentage of the total (2016).

Source: World Bank Report 2019

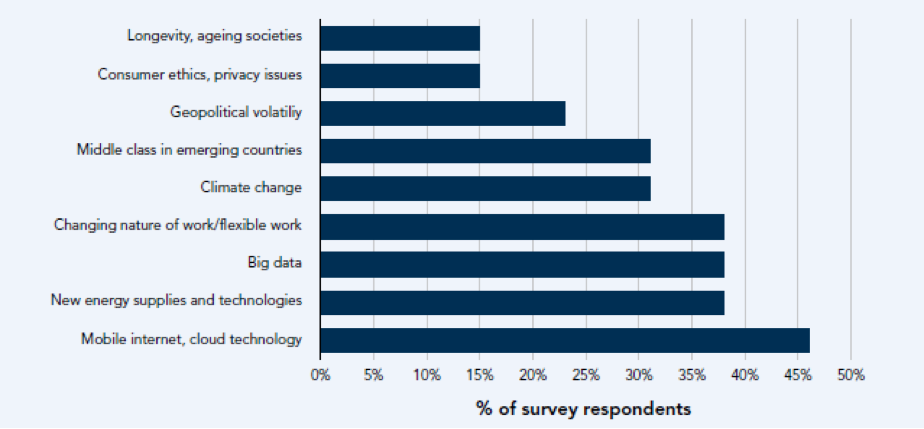

Figure 9: Important drivers of change impacting industries according to ASEAN business leaders

Source: World Bank Report 2019

Figure 10: Percentage of population using digital wallet (2016)

Source: World Bank Report 2019

Figures 7 and 8 show the importance to recognise the need to re-train and re-skill our employees compared to other Southeast Asian countries, Malaysia has a huge number of medium-skilled employees. However, we still lag behind Singapore when it comes to high-skilled workers. This discrepancy has informed MyDigital blueprint’s goals of building an agile, competent and highly skilled workforce for Malaysia. In re-training and re-skilling employees, Figure 9 shows a good estimate of various expertise required given that these are the important drivers of change impacting industries. The quality of re-skilling and training programmes is essential in setting the right direction for the adoption of digital capabilities. Accordingly, mobile internet connectivity, new energy technologies, automation, and data analytics will be paramount sectors. Additionally, flexible and remote working capabilities especially in finance, business, management, logistics and transportation, will help create more job opportunities.

Figure 10 shows the digital wallet usage across the region with Singapore being the highest, which again underlines the potential growth for other countries in the region and around the world.

OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES

There are always opportunities and challenges in any project or policy. Without a doubt, with MyDIGITAL, citizens will see its benefits in all aspects of education, communication, healthcare, businesses, public services and more. Although automation is often misconceptualised and oversimplified, the government wants to support small and medium enterprises (SMEs) to begin their respective automation processes.

To that end, the government has introduced smart automation grants to SMEs and mid-tier companies to cover up to 50% of the cost of automation, up to a maximum amount of RM200,000 under the PENJANA programme. It is pertinent for companies to automate selected processes to achieve efficiency and effectiveness despite the challenges. Furthermore, it is equally important for us to change our mindset about work and adapt to improve and optimise tools and techniques accordingly.

The current pandemic has shown us that organisations have had no choice but to automate including embracing online business platforms so that they can continue to serve the market. This is evident from the increase of online shopping and home-based businesses (especially in the retail, food and beverage industries) with direct home delivery services.

Banks and fintech startups engagements have also developed commercial partnerships where continuous improvisions are provided together with infrastructure and product support. Banks have also adopted digitalisation at various phases and distribution channels over the years and they will continue to develop and evolve in the next few years. The digital payment business has been growing strong with the rise of platforms such as FPX, Direct Debit, JomPay, Interbank Giro by 87% (y-o-y March 2021) complemented by efforts from the local banking sector to tap into online businesses. To that end, fintech startups play an important role in the country’s digitalisation process, not just in banking but also in other sectors.

It is common knowledge that Malaysia is good at outsourcing and providing global business services. However, more specific action plans are needed with the MyDIGITAL blueprint. What has not been mentioned in the document is the role of state governments, government-linked companies (GLCs) and government-linked investment companies (GLICs) as these entities facilitate many investments from corporate and capital markets. Thus, good collaboration and coordination among all entities are essential in creating and implementing an effective digital economy.

Thus far, policies and regulations governing businesses are clearer. For example, those that pertain to data analytics, big data, cloud computing and other themes alike. Public institutions are still uncertain about whether and how to implement big data given different expectations and understandings about its uses in public administration, its benefits and limitations, (a good example is in how to better manage the current COVID-19 pandemic) and how to further improve any public services. Usually, the maturity of a government’s digital services is reflected through how effectively it uses government data to create public services which are often characterised as “digital government”.

We have seen the government’s national digitisation initiatives (NDI) such as the electronic tax filing (e-Filing) system that was introduced by the Inland Revenue Board (IRB) in 2004. The system saw only a 5% adoption rate in 2006 but rose steadily to hit 15.3% in 2011. Nevertheless, it recorded a 33.5% growth in digital signature when IRB made it mandatory for employers to submit the Return Form of an Employer (Form E) via e-Filing. However, not every government agency or data provider is presently at the same pace when it comes to the information system and infrastructure readiness to adopt such practices at scale. MyEG, a flagship of government service provider comes close, but other agencies are still in various stages of investment and development when it comes to embracing digital platforms.

There are also other related issues or challenges when it comes to developing an open data policy, ranging from cybersecurity to data privacy concerns that need to be addressed. Beyond that, they also need to consider the standardisation of the data collected and released through the open data portal as well as how such data is defined and interpreted.

Open data is also divided into clusters which are organised by separate ministries and agencies. It is difficult to find the right data unless one knows the right agency that generates the open data as well as the quality and quantity of said data. There is a recommendation that having a feedback system on the open data portal will be useful in requesting unavailable data to create a data-rich ecosystem. Further, authorities can also work with specific sectors to collect and make available specific data that is unique to a specific sector. Representatives from the private sector and citizens will enable them to voice their actual needs and data can be collected to match the demand from the industry[1].

The most important question is how ready are our employers and employees in the country in managing this forthcoming digital economy transformation? There is a strong need to bridge the gap in high-skills workers that are critical to the economy. There ought to be specific programmes that can equip individuals to thrive in those pertinent skills and related industries as shown in Figures 7 and 9 respectively. This will enable us to attain real competitive advantage and value proposition not just from within the country but also globally.

Professor Dr. Loo-See Beh is the Head Department of Administrative Studies & Politics at Universiti Malaya. She is a Research Fellow with the National Human Resource Centre (NHRC) of HRD Corp.

The views expressed here are entirely the writer’s own.

References:

Malaysia Digital Economy Blueprint (2021). Putrajaya: Economic Planning Unit.

The Edge, 15 March 2021

The Edge, 3 May 2021

World Bank Report (2019). The Digital Economy in Southeast Asia – Strengthening the Foundations for Future Growth. Washington D.C.: The World Bank.

[1] The Edge, March 15, 2021