Introduction

We are seeing rapid changes in today’s business environment, with mounting turbulence and uncertainties. With such circumstances, it is difficult for organisations to make a reliable prediction of the future in order to develop their long-term business plans. Thus, firms are under great pressure to develop new strategies and make speedy decisions to navigate these constant changes.

In view of the increased rate of change, there is a need for a fast and immediate response, which necessitates broader organisational flexibility. Such scenarios have enhanced the network of talented employees and their contribution to the decision-making process. Employee participation in the firm’s management leads to potential innovation, which in turn will facilitate opportunity and recognition in the organisation. To reciprocate, managers provide opportunities for participation of subordinates in decision-making based on their merits as it has been proven by researchers to improve organisational performance

Beyond this, competitive pressures, subsequent changes in work organisation and the current global political climate have led to the growing emphasis on all forms of flexibility in various industries and these have impacted the way and models of participation are implemented in organisations.

Meaning of employee participation

Employee participation (EP) is defined as the process where employees are involved in the decision-making processes, rather than simply acting on orders, and is a part of the process of empowerment in the workplace (Parasuraman 2017). On the other side of the coin, employee involvement (EI) can be defined as direct staff participation to help an organisation fulfil its mission and meet its objectives by applying their ideas, expertise, and efforts towards solving problems and making decisions. If we scrutinise these two definitions closely, there is an overlap of meaning, making the two terms interchangeable. Thus, for the purpose of this paper, the terms participation and involvement will be used interchangeably. Parasuraman (2007) postulates that employee participation refers to the wide variety of policies, mechanisms, and practices that enable employees to take part in decision-making, frequently at the level of the enterprise or workplace.

In Western countries, based on studies by Todd and Peetz (2001); Frenkel and Kuruvilla, (2002); and Parasuraman and Jones (2006), employee participation is a common practice. Indirect employee participation such as Joint Consultative Committees and Collecting Bargaining are only practised in large organisations. It was also reported that trade unions and employees influence in the workplaces are very limited (Todd & Peetz, 2001; Frenkel & Kuruvilla, 2002; Parasuraman & Jones, 2006). It was observed that in literature, research related to the practice of employee participation in Malaysia’s local companies as well as multinationals are relatively low, except for few studies conducted by Rose (2002), Parasuraman and Jones (2006) and Parasuraman (2007).

Employers are constantly seeking more efficient, effective, and flexible means of production to overcome the continuous change in product and service markets. This is done in light of very strict demands on quality especially due to Covid-19 and the ensuing MCOs.

Under these changing conditions, say Summers & Hyman, 2005, it is not surprising that employers, policymakers and employees themselves show very deep concern in safeguarding and promoting their interests and these have been reflected in different approaches to employee participation.

Different Forms of EP in the workplaces

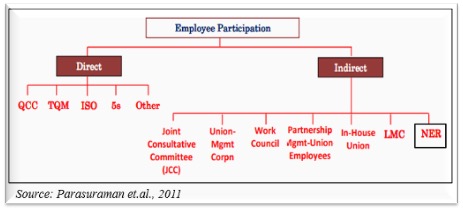

The study of Parasuraman (2007) shows that different direct forms of employee participation are present in workplaces. These include quality circles, total quality management, MS ISO 9000, employee suggestions scheme (ESS), 5S, teamwork, team briefings, problem-solving teams, formal meetings, informal meetings, face-to-face communications, and daily walks by senior managers. On the other hand, indirect forms of employee participation are the joint consultation committee (JCC), Management-Union Committee, Safety, and Health Committee, Sports and Recreation Committee, and Collective bargaining.

The study also reveals that the direct forms are mainly on quality, productivity, management-employee relationship, problem-solving methods, and the enhancement of customer satisfaction in relation to products and services. , The indirect forms, on the other hand, are mainly implemented to improve health and safety procedures, enhance union-management relations in order to avoid misunderstanding between parties, and encourage the participation of non-managerial employees in social and recreational activities.

Therefore, employee participation can be seen as an umbrella title that covers a wide range of practices that potentially serve different interests. Any study on ‘employee participation has to delve into terms as wide-ranging as industrial democracy, cooperatives, employee share schemes, employee involvement, human resource management (HRM) and high-commitment work practices, to collective bargaining, employee empowerment, teamwork, and partnership to capture the full picture of participation.

There are obvious problems associated with having so many different interpretations, and consequently, results associated with different meanings of participation may also vary. Furthermore, the advantage enjoyed by one social partner may not necessarily be received as universally advantageous by other partners with interest in the employment relationship. In other words, participation can be seen as ‘contested terrain [territory]’.

The term ‘employee participation’ can be divided into two primary categories; financial and work-related participation. Financial participation schemes are split into two main dimensions. The first dimension entails the distribution of shares to employees, based on the assumption that share ownership encourages positive attitudinal and behavioural responses. The second dimension of financial participation concerns flexibility of pay, where an element of remuneration varies with profitability or other appropriate performance measures. One such example is cash-based profit-related pay (PRP), in which income tax relief is offered to schemes that meet Inland Revenue requirements.

According to Summers and Hyman (2005), work-related participation can be divided into several forms: individual or collective, and direct (i.e., face-to-face) or indirect (i.e., through a representative) participation. These can be grouped into two main types of work-related participation. The traditional collective participation aims for a more equitable distribution of power throughout the organisation. While the ‘new’ forms of participation are more direct and individualised and have tended to grow out of management strategies, such as HRM. The aim is to secure employee commitment to organisational objectives through sophisticated communication procedures and individualised reward and developmental initiatives such as performance appraisal linked to PRP. Direct and indirect EP is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Direct and Indirect of EP Forms

The Factors for Introduction of EP in the organisation

There are various different competing reasons for implementing employee participation. Poutsma (2001) identified four dominant ways of employee participation and involvement comprising humanistic, power-sharing, organisational efficiency and redistribution of results rationales. In another instance, Summers and Hyman (2005) categorise employee participation under three main operational rationales, namely economic, social and governmental. Employees can also participate in making financial decisions operating through the economic rationale to which it is closely associated to. As suggested by Creigh, et al (1981), “financial participation measures promise to exert fundamentally positive effects at the workplace through removing, or at least minimising boundaries between employer and employee by offering the latter ‘a stake in the firm”. While much theoretical work points to the existence of powerful links between business performance and workplace innovations, especially high-performance workplace practices (HPWPs) such as employee involvement and profit-sharing, often theorists disagree over the size, direction, and nature of such links (Jones & Kato, 2005). Besides, past studies have found that there has been no association between employee participation and firm performance be it positive or a negative association between the two dimensions (Summers & Hyman, 2005).

Some past literature also supported that employee participation is one means to improve performance but varies between industrial sectors. However, even though participation has had an overall positive effect, this effect was not significant for some industries, (such as footwear), but is instead slightly more significant in the clothing sector. Further, this variation in outcome is subjected to the type of participation involved. For instance, Defourney, et al. (1985) indicated that the productivity enhancement as a result of employee participation yields the strongest outcomes in converted firms as compared to in organisations operating in the form of co-operatives. These findings suggested that the relative increase in employee participation is an important explanatory factor that influences the firms’ performance and productivity.

However, there are different outcomes for different forms of participation. For instance, in a labour-managed firm, it was revealed that there is a small rise in productivity, whereas participation had no significant impact on productivity in participatory capitalist firms. This suggests that the degree of employee influence and participation predicts to some extent the successes of participation schemes initiated by the organisations. Furthermore, research also found that enforced co-determination had a negative effect on productivity, indicating that forced participation may not be effective.

But the question remains, why should the type of participation introduced affect performance differently? This body of contradictory evidence is not surprising because there is a considerable lack of attention given to the mechanisms by which employee participation can influence performance and the assumptions made about causality, linking participation to improve performance. There are also assumptions made that participation induces greater employee association with management values and that this will also improve employment relations within the workplace. If this assumption is not strong, there is doubt that the assumed positive links between participation and performance can exist (Summers & Hyman, 2005).

There are doubts concerning the performance effects of high-performance work practices and controversies surrounding the effects of worker representation. However, the worker representation literature indicates that the effect of unions on productivity is likely to be small on average. Therefore, we should look to factors such as innovative work practices in explaining the diversity in the effects of worker representation in different settings (Addison, 2005).

Some studies indicated that non-managerial employees are increasingly involved in workplace decision-making. These changes which are not limited to a specific economic context but are more structural in nature, have a real potential for enhancing productivity. However, some conditions are necessary for sustaining and stimulating workplace innovation. One, if innovative work systems are not supported by arrangements that foster mutual gains and good working conditions, they may lead to inequality and social tension. Two, putting social arrangements which are more conducive to trust and social capital in place will lead to further organisational innovation and economic growth.

Findings from a study done by Alsughayir (2016) showed a significant positive relationship exists between participation in decision making (PDM) and firm performance, suggesting that PDM is an essential component in influencing firm performance. The higher the level of employee participation in decision-making, the higher the level of firm performance.

For example, in the Malaysian context, Trade Union Act 1959, the Industrial Relation Act 1967 and Employment Act 1955 govern indirect employee participation in Malaysia. However, the Ministry of Human Resources in conjunction with the Malaysia Councils of Employers Organisations (MCEO) and the Malaysia Trade Union Congress (MTUC) drew up the Code of Conduct for Industrial Harmony in 1975. The aim of this Code of conduct was to lay down principles and guidelines for employers and workers on the practice of industrial relations for achieving greater industrial harmony. This Code of conduct emphasizes employee participation and is also used as a reference in the Industrial Court. Nevertheless, this code of conduct is not legislation and is therefore not widely used by employers(Parasuraman, 2014).

Conclusion and A Way forward

In order to enhance and improve the employer-employee relationship, a combination of direct and indirect forms of employee relations and involvement can contribute to the best organisational results. As indicated by Gollan and Markey (2001), direct and indirect forms of participation are mutually supportive as the EPOC (Employee Participation in Organisational Change). The studies of Parasuraman and Jones (2006) and Parasuraman (2007) conducted in large Malaysian companies reveal that employee participation is implemented and enforced through Joint Council Consultative Committee and collective bargaining, but is limited to some extent. The union and non-managerial employees’ capacity to influence the management’s final decisions are still questionable. The final decisions are still in the hands of the management and this is why Pateman (1970) referred to it as ‘pseudo participation’ where management has already made the final decisions and they only persuade unions and employees to accept their decisions.

In summary, Parasuraman, et. al. (2007, 2014) further cautioned that even though the positive effects of employees are acknowledged in the Dutch subsidiary, it can be concluded that the extent to which employees have an influence in the company is limited, and this assumption is in agreement with Cotton et al (1988). Information is shared with employees, and they can give their opinion about the decision, although this is mainly through the Works Committee. Employee participation basically focuses on the job level, and sometimes on the departmental level. However, at the organisational level, employees hardly have an influence on indecision-making. Through the Works Committee, they could have an influence, but this committee is most of the time only involved in the sense that they are informed when the policies have already been drawn up.

Employee participation is a key tool in the workplace, especially during Covid-19. Employers and employees (union) can utilise EP as a platform to discuss, make decisions that benefit both employers and employees, enhance industrial harmony, improve productivity, and finally adopt good industrial relations and HR practices in the workplace. Malaysia aspires to be a high-income nation. Therefore, innovative management practices such as EP should be encouraged and supported strongly by employers, unions, and the government.

Professor Dr. Balakrishnan Parasuraman is a Professor of Management/ HR/ Industrial Relations at the Faculty of Entrepreneurship and Business, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan (UMK) based in Kota Bahru, Kelantan. He is a research fellow of the National Human Resource Centre (NHRC) of HRD Corp. The writer wishes to acknowledge Mr Firdaus Nizam for assisting in this research.

The views expressed here are entirely the writer’s own.