The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a multifaceted turmoil for the nation, including an economic slowdown with employees losing jobs and facing pay cuts, especially for low-wage earners. In Malaysia, the situation is made worse by inflation and the rise in cost of living. This has led to a fall in the average monthly wage. In response to the situation, there have been calls to increase the minimum wage to help Malaysian workers cope with the current economic challenges. The government announced the implementation of the minimum wage at the rate of RM1,500 a month on 1 May 2022.

Presumably, when there is an increase in the minimum wage rate, productivity growth is expected to rise in tandem. This report discusses the impact of the living wage, minimum wage and labour productivity in the Malaysian context.

The National Wage Consultative Council was established to conduct studies on all matters concerning minimum wage and to make a recommendation to the government. The Minimum Wage Order 2012 was then formed and enforced on 1 January 2013 with a monthly minimum of RM900 for Peninsular Malaysia and RM800 in Sabah and Sarawak. Throughout the years, the minimum wage has been revised four (4) times.

On 1 May 2022, the government announced the implementation of a new minimum wage of RM1,500 per month. However, the issues revolving around the new minimum wage are still a point of contention among politicians, employers, workers, and analysts.

From the employees’ perspective, an increase in the minimum wage is required to offset the rising costs of products and services, that has led to an increase in the cost of living. Among the local population, this wage increase is expected to raise the rate of labour force participation.

However, according to employers, particularly Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) and those still impacted by the COVID-19 outbreak, a 25% increase in labour expenditures (from a monthly wage of RM1,200 to RM1,500) is expected to put pressure on their operating costs. Rising prices of goods and services, and a reduction in the number of workers are among the market responses that are expected to occur when the higher costs cannot be offset by an increase in revenue. It should also be noted that no nation in the world experiences a perfect correlation between labour productivity and wages.

According to the Global Wage Report 2020 by International Labour Organization (ILO), globally, an estimated 327 million wage earners are paid at or below the applicable hourly minimum wage. This figure represents 19% of all wage earners and includes 152 million women. Although in absolute numbers, more men than women earn minimum wage or less, women are over-represented among this category of workers.

For example, while women make up 39% of the world’s employees paid above the minimum wage, they represent 47% of the world’s sub-minimum and minimum wage earners. The extent to which a minimum wage may reduce wage and income inequality depends on at least three key factors:

Although the primary purpose of minimum wage is to protect workers against unduly low pay, it can also contribute to reducing inequality under certain conditions. The first condition comprises the extent of legal coverage and the level of compliance – which, when combined, may be called the ’effectiveness’ of minimum wage.

Second, the level at which minimum wage is set plays a crucial role. Finally, the potential of minimum wage systems for reducing inequality depends on the structure of a country’s labour force, particularly whether workers with low labour incomes are wage workers or self-employed, and the characteristics of the beneficiaries of the minimum wage – in particular, whether they live in low-income families.

In conjunction with HRD Corp Open Day in Sarawak last 5 July 2022, HRD Corp organised the National Forum Series, titled Malaysia at the Crossroads: Living Wage v Minimum Wage, and Its Impact on National Productivity.

The forum featured the Chief Statistician Malaysia, Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM), the Deputy Director, Department of Labour Sarawak, the Executive Director of the Malaysian Employers Federation (MEF), the Director of Malaysia Productivity Corporation (MPC) Sarawak Region, and the Vice President of the Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers (FMM). The topic was discussed in great depth.

Living Wage ‘vs’ Minimum Wage

There is no consensus on the agreed definition of a living wage as a concept and there is no globally accepted dollar amount that defines it. Nevertheless, there is common ground on what constitutes a living wage — it is a wage that enables workers and their families to meet their basic needs.

According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), a living wage or living income is the local remuneration received for a standard workweek that is sufficient to afford a decent standard of living for a worker and their family. It should be enough to provide for all basic needs, as well as some discretionary income and provision to cover unexpected events.

According to the ILO, living wage refers not just to the existence of a minimum level of remuneration, but also to a minimum and acceptable standard of living.

In addition, the United Nations Global Compact defines living wage as a remuneration received for a standard workweek by a worker in a particular place sufficient to afford a decent standard of living for the worker and their dependents.

On the other hand, Bank Negara defines living wage as the ‘minimum acceptable standard of living which goes beyond being able to afford the necessities, such as food, clothing, and shelter. This standard of living should include the ability to participate in society, the opportunity for personal and family development, and freedom from severe financial stress.

At the same time, it should reflect needs, not wants. It does not capture the cost of lifestyle, which is the spending to fulfil the desires for an aspirational living standards.

On another spectrum, the government has introduced a more structured policy for a wage-fixing mechanism commonly known as the minimum wage. The ILO defined the minimum wage as the minimum amount of remuneration that an employer is required to pay wage earners for the work performed during a given period, which cannot be reduced by collective agreement or an individual contract. Some developing nations have started to define salaries from a wage viewpoint. The indication for the definition may be the minimum wage, the living wage, or the median wage.

ILO reported that the minimum wage is around 55% of the median wages in developed countries and 67% of the median wages in developing and emerging countries, on average. At RM1,500, the percentage of Malaysia’s minimum wages to the median salaries and wages increased to the range of 60.0% to 72.7% (58.2% in 2020). Although the percentage of minimum wages to the median salaries and wages increased tremendously, the living wages are almost two-fold from the minimum wages in Malaysia.

To put things into perspective, companies these days are expected to go beyond the wage legislation of minimum wage. This could be true as many countries reported that the minimum wage does not necessarily allow for a decent living. For example, according to the Bank Negara, more than 25% of households in Kuala Lumpur earn below the living wage.

The Malaysia Economy Landscape

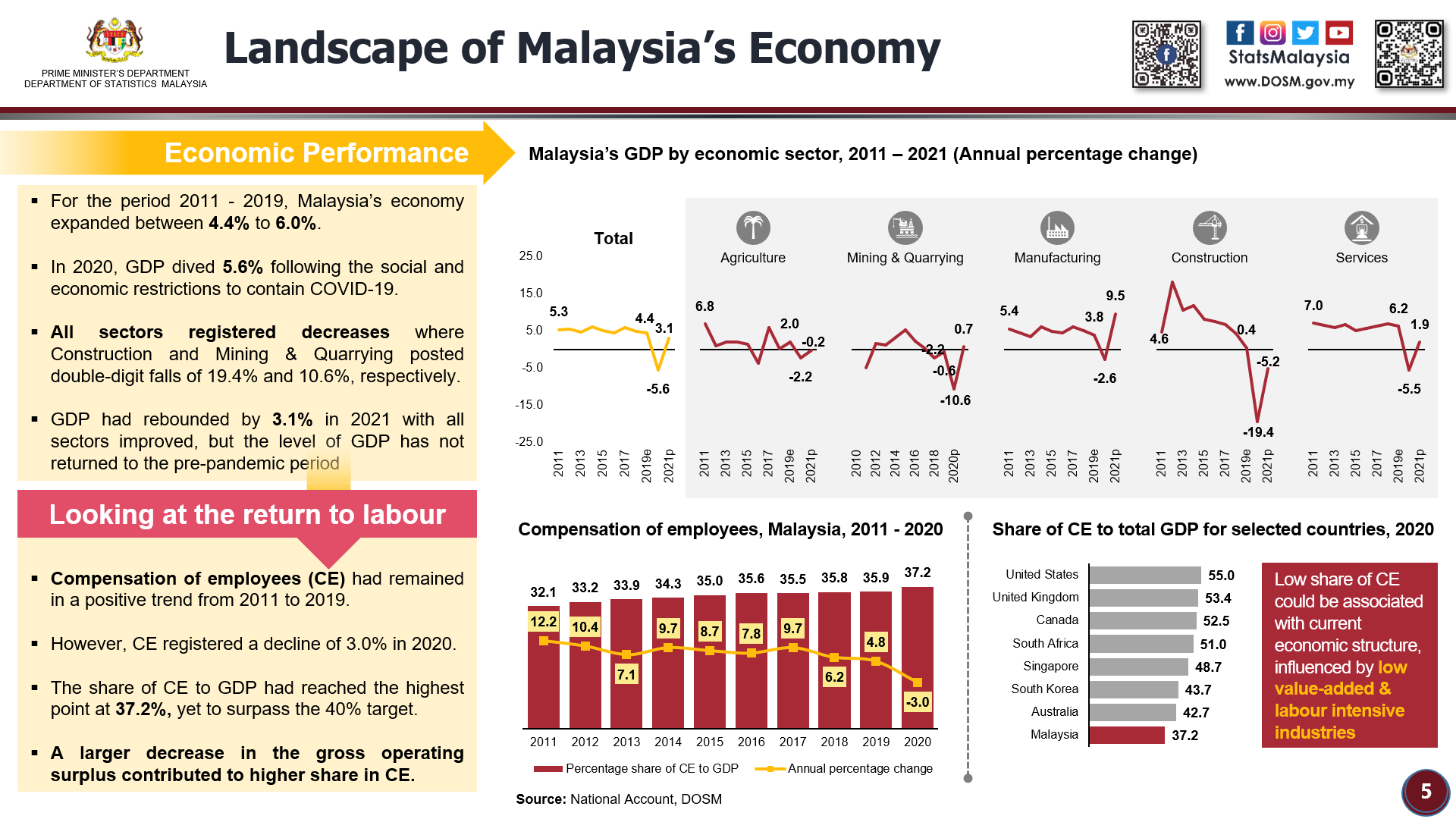

Our economy is a broad-based economy that consists of manufacturing, agriculture, services, and other sectors. For the period between 2011 to 2019, Malaysia’s economy expanded between 4.4% to 6.0% per annum. The GDP fell to 5.6% in 2020 as a result of the social and economic constraints imposed to contain COVID-19.

All sectors recorded a decline in growth, with the construction and mining and quarrying sectors posting double-digit falls of 19.4% and 10.6%, respectively. The GDP had rebounded by 3.1% in 2021 with all sectors improving. However, these sectors have yet to return to the levels enjoyed in pre-pandemic times.

Compensation of Employees (CE) remained on a positive trend from 2011 to 2019. However, CE registered a decline of 3.0% in 2020. The share of CE to GDP had reached the highest point at 37.2%. But it has yet to surpass the 40% target. A larger decrease in the gross operating surplus contributed to a higher share in CE.

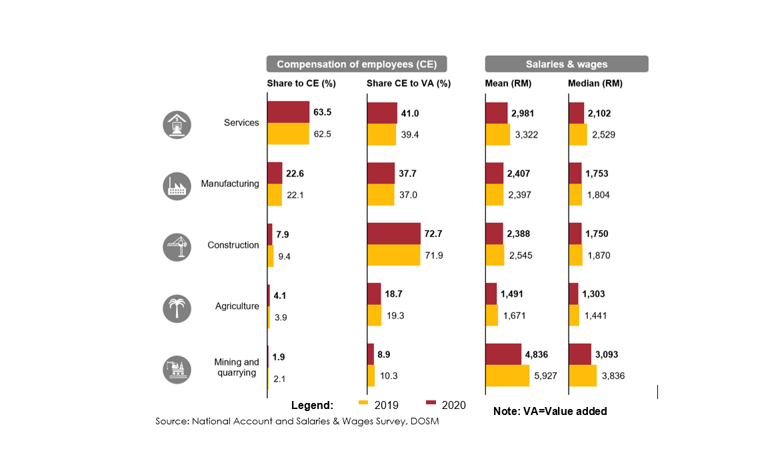

As the major contributor to Malaysia’s economy, CE in the services sector made up 63.5% in 2020. The share of CE to VA (Value Added) for the services sector was 41.0%, with mean monthly salaries and wages of RM2,981.

The CE to VA for the manufacturing sector was 37.7%, while the mean monthly salaries and wages were RM2,407. The construction sector registered the largest share of CE to VA at 72.7%, considering the higher reliance of this sector on labour. The mean monthly salaries and wages received by paid employees in the construction sector was RM2,388. The share of CE to VA for the agriculture sector was 18.7%. Employees in this sector received the lowest mean monthly salaries and wages of RM1,491.

The lowest share of CE to VA for the mining and quarrying sector is at 8.9%, following the influence of capital intensive of the oil and gas industry. Mean salaries and wages were RM4,836 per month, which was the highest among all these economic sectors.

The labour force is improving with the increase in employment and the decline in unemployment rates. The job market has recorded a recovery, indicated by an increase in the number of filled jobs, which is in line with the expansion of global and domestic activity. Both labour productivity per hour worked and labour productivity per employment remain on a growth trajectory.

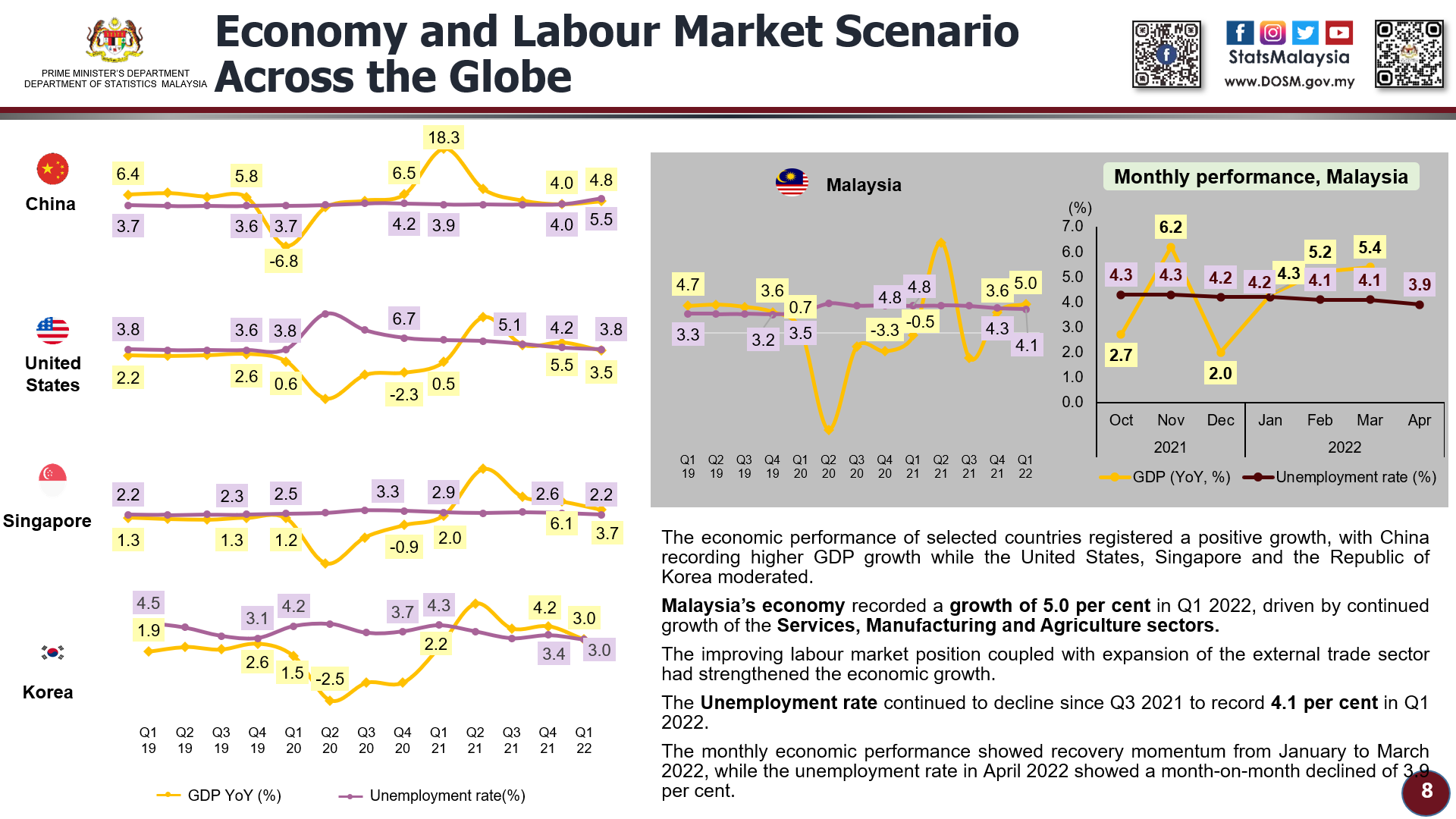

The economic performance of selected countries registered growth, with China recording a higher GDP growth while the United States, Singapore, and the Republic of Korea growing at a more moderate pace.

Malaysia’s economy recorded a growth of 5.0% in Q1 2022, driven by the continued growth of the services, manufacturing, and agriculture sectors. The improving labour market position coupled with the expansion of the external trade sector has strengthened economic growth. The unemployment rate continued to decline since Q3 2021 to 4.1% in Q1 2022.

The monthly economic performance showed a momentum in recovery from January to March 2022, while the unemployment rate in April 2022 showed a month-on-month decline of 3.9%.

In 2020, Malaysia recorded its first decline in the nominal value of salaries and wages since 2010. The value-added per employment during the pandemic period is still below that of 2019 levels. Although labour productivity per hour worked in 2021 declined compared to 2020, the value of productivity was higher than in 2019, indicating an increase in efficiency.

In Q1 2022, both labour productivity per employment and hour worked increased by 2.7% and 0.5%, respectively, due to the lower value base recorded in the previous year.

Minimum Wage Implementation Around the Globe

Malaysia’s new minimum wage of RM1,500 (USD355), which is equivalent to RM7.80 (USD1.84) per hour with a maximum of 48 working hours per week, is still far behind in comparison to other countries. On average, from 2011 to 2020, the real wage growth in Malaysia has outpaced productivity. The strength in wage growth in Malaysia suggests that employers compensate workers more appropriately for the output produced, improving the wage-to-productivity ratio.

By sector, the productivity of agricultural activities grew marginally high, although real wages are stagnant. Meanwhile, the productivity of the manufacturing sector grew as fast as real wages, indicating that increasing additional revenue by hiking the wage rate is equal to hiring new workers.

Although sector-wide minimum wage cushioned the wage inequality in the country, we are still compensated quite unfairly for our productivity.

In the year before the pandemic (2019), studies found that Malaysian workers are paid less than workers in the benchmark economies.

Impact of Productivity on Wages

As productivity grows and each hour of work generates more and more income over time, productive workers are recognised through salary increases. Incentives are a useful tool to further encourage productivity which will then translate to higher wages.

By directly linking wages with productivity, the employee is continuously rewarded for hard work, which drives them to generate more profit for the business. Highly productive employees also have greater job security. Workers that maintain a positive return on a company’s investment will continue working and receiving wages.

The movement in wages should be determined by market forces. Having a system that establishes a closer link between wage and productivity will enhance competitiveness and ensure that wages continue to increase. It provides flexibility and competitiveness in both good times and bad times while ensuring job security and adopting minimal cost-cutting measures.

Comparison between Malaysian and South Korean Labour Productivity

South Korea’s Gross National Income (GNI) per capita was USD280 in 1970 and reached more than USD27,000 in 2016. South Korea has become the 14th largest economy in the world based on a report by the World Bank in 2018. South Korea enjoyed economic prosperity and became a high-income country. It underwent major changes in economic policy during the 1980s and 1990s with a focus on economic stabilisation through policy and legislation that are geared towards growing its technology-based industries.

On the other hand, the GNI per capita for Malaysia was USD370 in 1970 and only reached USD 9,860 in 2016. Malaysia is still struggling to break free from the middle-income trap.

Higher labour productivity was one of the factors which enabled South Korea to become a high-income nation. The average annual growth of labour productivity for South Korea had consistently surpassed Malaysia’s since the 1970s. The average annual growth for Malaysia was 2.7% while South Korea expanded by 4.4% per annum for the period of 1982 to 2016.

The average annual growth of South Korea’s capital intensity was 5.7% per annum for the period of 1982 to 2016, which is higher than Malaysia’s that grew at 3.7% during a similar period. The strong growth of South Korean capital intensity particularly during the 1970s to 1990s was supported by higher capital accumulation, which was doubled.

The Impact of Implementing Minimum Wage on Productivity

Implementation of minimum wage is believed to boost employee motivation. Minimum wage led to ’efficiency wage’ where employees consistently provide higher effort levels in response to higher wages. Besides that, it could help in retaining and training existing employees in an organisation.

In addition, minimum wage can increase a firm’s total factor productivity, consistent with organisational change, training, and efficiency wage. It could also encourage firms to adopt more capital-intensive production technologies and embrace IR 4.0 technologies.

This can raise the overall efficiency of the economy through competition when a firm with higher productivity moves up the value chain by replacing a firm with lower productivity.

In a nutshell, Malaysia’s new minimum wage is still far behind other countries. Although it has been proven that the minimum wage has cushioned the wage inequality in the country, employees are still not compensated fairly for the work done. This is reflected in the report where Malaysian workers are paid less than workers in benchmark economies like South Korea.

The panellists believe that minimum wage could help reduce wage dispersion and channel productivity gains into higher wages, contributing to higher labour productivity. The adoption of innovation and automation technology will increase efficiency and productivity as well as uplift the current labour market structure in the long run. It is anticipated that the government will incentivise investments and offer tax incentives to businesses that adopt automation and technologies to boost productivity.

The effort to bolster productivity could also be channelled through the formation of Sectoral Training Funds (STFs) to upskill the workforce and promote productivity, especially among the MSMEs. Sectoral training can equip workers with up-to-date industry-wide skills, enable knowledge sharing and increase business productivity. This has been proven to work in countries like Belgium, Denmark, and the Netherlands. The STFs training initiatives are based on the needs of employers and the labour market.

Ultimately, the panellists highlighted that there is an equilibrium point between salaries and productivity that can only be realised by the cooperation of all relevant parties, including the government, politicians, employers, and employees.

Reinventing Human Capital Growth for a Sustainable Future

For more information, please contact:

Tel: 1800-88-4800

Fax: 03-2096-4999

Disclaimer: HRD Corp shall not be liable for any loss or damage caused by the use of any information obtained from this website.

Copyright © 2025 HRD Corp All rights reserved |